4. Torrington Castle – Burn burn burn!

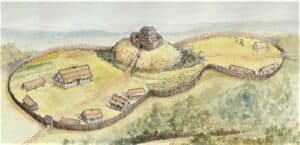

Beorhtric’s manorial compound would have been occupied and then altered and dismantled by Odo and in c.1090 he started building a typical Norman motte and bailey castle on top of the hill at the highest point. We don’t know the extent of any early fortifications built by Odo, it was his son William FitzOdo de Toriton who built the substantial site we see surviving as earthworks today.

The grassy earthen ramparts in front of you, enclosing the top of the hill and around the car park represents the remains of this early castle. The castle remains now comprise an inner bailey (the car park banks) and outer bailey (the banks below the stone walls of the bowling green) and a motte mound (the large mound next to the bowling green, which the path runs up and over and is truncated).

The first castle at Torrington would have had a wooden keep (tower) on top of the mound which was both a lookout and the main defensive stronghold in case of attack. This tower would have been vital to the role of the castle controlling the valley. Walk along the path onto the commons and you can see the vast view a tower would have had, as none of the trees would have been present! We must remember that the Normans were a hostile invading force and whilst we think of castles as traditional to Britain now, they were a shockingly new form of structure, never seen before by the people of Torrington and intended to intimidate them.

A royal document of 1139 records the castle as Torrington being burnt to the ground in a battle during the civil war known as ‘The Anarchy’. This castle was noted as having a tower and other unspecified buildings. Obviously, as we know it was burnt the castle was still timber at this stage, suggesting the permissions for the Barons to rebuild in stone was probably repeatedly denied by the various kings. It strongly defensive position may have made it considered to be impregnable in stone and it may therefore have been considered too dangerous to allow a powerful Devon Baron that advantage.

Living in a castle would have been tough for the occupants; castles weren’t grand in this early period. The structures inside the banked enclosures would have been little changed from the Saxon houses in the town, with a series of wooden framed and cob buildings scattered throughout, for living, sleeping, cooking and storage, with a central Hall, being the administrative centre. People would have had to walk between the different buildings; just imagine how cold it would have been in winter! There may also have been some animal pens and barns. The outer bailey would have had a barracks or accommodation for the men at arms and possibly stables.

The defences of the castle had an outer enclosure, ‘the outer bailey’ and an inner enclosure, an ‘inner bailey’. The modern name Barley Grove of the area and car park is a corruption of ‘Bailey’ and indicates a surviving local folkloric connection to the site of the former castle, even when ruined. The defences themselves were of massive posts forming fences on the earth and stone-built ramparts of the two baileys, called palisades. The ramparts had a deep ditch around the outer edge and possibly even a second bank beyond. The ditch would have been created partially by digging out soil and rock to make the bank(s). Ditches on early castles could be filled with water, more like a moat or could be dry, merely inconvenient and emphasising the height and steepness of the bank, aiding the palisade in its defensive function. In areas where defence was vital the ditches may be filled with stakes.

You can still walk around the remodelled castle ditch by following the sunken path from the commons up to the pannier market, turning right and walking out towards castle street; this rounded sunken roadway runs along the in-filled bottom of the original ditch. The tall banks have been altered but still stand to as much as 2m in places.

Historic documents suggest the castle defences weren’t built in stone until the 1200s and were then mired in controversy. This suggests it remained as a timber and earthen banked structure far longer than other castles, such as at Launceston, which is a good local example. The buildings inside the enclosures may have been rebuilt in stone and cob and advanced in architecture along the lines of other aristocratic buildings, separate from the Norman defences.

Odo and the de Toriton family

Odo became a powerful landowner through his uncle gifting him many manors and estates. He cemented his role by marrying Fila, the daughter and heir of another powerful Norman lord, Tetbald FitzBerner, who had also been given land in Devon by William the Conqueror.

This dynastic marriage united Odo’s twenty-four manors with Tetbald’s twenty-seven manors and created the Feudal Barony of Great Torrington. This became one of the eight great medieval Baronies of Devon. The new family adopted the surname ‘de Toriton’. The de Toriton family dominated Torrington and were influential in Devon between the 1090s and 1226. They were also known as the FitzOdo family in the early years as it seems Odo’s illegitimate son William inherited the Torrington holdings. The family’s power increased when in 1198 John, Baron of Torrington became Sherriff of Cornwall.

The first civil war to affect Torrington was known as ‘The Anarchy’ (1135-1153AD), a fight for succession between the formers king’s daughter, Matilda and her cousin Stephen. The Barons de Toriton, supported Stephen in the war, against Matilda. Torrington and the wooden castle were attacked and burnt to the ground. The de Toriton family later had to pay a fine and ask for a pardon from Matilda’s son and the castle was rebuilt.

On 27th August 1216 William IV Baron of Torrington was Attained; which means all of his lands, possessions and money was taken by the King as a punishment. William and other Barons fought against King John I, who was trying to resist the rules imposed by Magna Carta, during the First Barons War 1215-1217.

Later in 1221 there was another crisis; when William went on to fortify the castle’s outer ramparts with new stone walls. This was known at the time as an illegal or adulterine castle. King Henry III was furious, as he was trying to restrict the power of Barons. An order was also sent out to demolish the castle. The Sheriff of Devon was sent with a troop of soldiers. Not only were the walls demolished but the moat was partially in-filled and the ramparts dug away. The castle site was abandoned.

Matthew, William’s uncle, inherited when William died young. Matthew paid a fine of 100 pounds, which relates to about 192, 000 pounds today and got back the Devon estates. He was the last Baron of Torrington, dying in 1226 with no heirs. The estate was split between his five sisters and their children.

For further reading on the Castle and an overview of what is happening with it please use this ‘Dig the Castle’ link to go to our sister website pages.

Links and further reading

The Anarchy – Stephen and Matilda

History Extra website for BBC History and Magazine

https://www.historyextra.com/period/medieval/guide-the-anarchy-what-civil-war-stephen-matilda/

Medieval Castles – English heritage – links to info and sites to visit

https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/learn/histories/medieval-castles/

Ancient History.net – Motte and Bailey castles – uses nearby Launceston Castle as an example

https://www.ancient.eu/Motte_and_Bailey_Castle/

English Heritage guide – the archaeology of early motte and bailey castles

https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/inspire-me/blog/blog-posts/2017/how-to-spot-a-castle-hiding-in-plain-sight/

British Library – Magna Carta

https://www.bl.uk/magna-carta?gclid=EAIaIQobChMIvfOb8ZzY7gIVRertCh3mUAJ-EAAYASAAEgL8pvD_BwE

School Resources – mixed key stages – Castle, Magna Carta and Medieval Times

English Heritage – The Norman Conquest – info and resources

https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/members-area/kids/norman-england-pma/

School History Website – Motte and Bailey castle activity

https://schoolhistory.co.uk/medieval/motte-and-bailey-castle-activity/

BBC History – Castles lessons plan etc

https://downloads.bbc.co.uk/schools/primaryhistory/lesson_plans/anglo-saxon/normans_lp_hoh_castles.pdf

Study.com website – Norman castles – Facts and Information page

https://study.com/academy/lesson/norman-castles-in-england-lesson-for-kids-facts-information.html#:~:text=The%20Normans%2C%20led%20by%20William,in%20London%20and%20Rochester%20Castle

National Geographic Kids – Meet the Normans resources and activities page

https://www.natgeokids.com/uk/primary-resource/meet-the-normans-primary-resource/

National Archives – Norman Castles – teaching resources – key stage 4 https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/medieval-castles/

BBC History – video – The Rise of the Plantagenets – Key Stage 4

https://www.bbc.co.uk/teach/class-clips-video/history-gcse-the-rise-of-the-plantagenets/z4krkmn

Schools History website – The Anarchy – teaching resources

https://schoolshistory.org.uk/topics/british-history/normans/king-stephen/

English Heritage – Build a Norman castle in Minecraft

https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/learn/1066-and-the-norman-conquest/build-a-norman-castle/

British Library website

Teaching Resources – The Context of Magna Carta – Link to PDF/Power-point

https://www.bl.uk/teaching-resources/mc-magna-carta-medieval-context

British Library website

Teaching Resources – What is Magna Carta – animation for younger children – primary

https://www.bl.uk/magna-carta/videos/what-is-magna-carta

British Library website

Teaching Resources – 800 years of Magna Carta – what is mean and means today – animation – Secondary age

https://www.bl.uk/magna-carta/videos/800-years-of-magna-carta

British Library website

Teaching Resources – Women in History – Women and Magna Carta

https://www.bl.uk/teaching-resources/mc-did-magna-carta-apply-to-women

HER National Records for Medieval Castle – Torrington Castle

HER number: MDV18797

Name: Great Torrington Bowling Green

Text: Bowling Green dating from 1645 to the east of Great Torrington Castle, with 18th century walls and gazebo. May be on the site of the medieval eastern bailey of the castle.

Link to official record: https://www.heritagegateway.org.uk/Gateway/Results_Single.aspx?uid=MDV18797&resourceID=104

HER number: MDV438

Name: Borough Boundary Stone, Castle Street

Text: Borough boundary stone formerly built into wall near Castle house.

Link to official record: https://www.heritagegateway.org.uk/Gateway/Results_Single.aspx?uid=MDV438&resourceID=104

HER number: MDV13834

Name: Great Torrington Castle Chapel

Text: Medieval chapel of St James at Great Torrington Castle, converted into a school in the 17th century. A school house was built by Lord Rolle, on or near the site of the chapel, in 1834.

Link to official record:

https://www.heritagegateway.org.uk/Gateway/Results_Single.aspx?uid=MDV13834&resourceID=104

HER number: MDV437

Name: Great Torrington Castle

Text: Great Torrington Castle, mentioned in documents in 1139 and 1228, but subsequent history uncertain. Remains of stone buildings and a rampart identified to the east of the Bowling Green.

Link to official record:

https://www.heritagegateway.org.uk/Gateway/Results_Single.aspx?uid=MDV437&resourceID=104

HER number: MDV18346

Name: Former pound, Great Torrington, Castle Hill

Text: Great Torrington Pound, a rectangular enclosure on Castle Hill with stone rubble walls.

Link to official record:

https://www.heritagegateway.org.uk/Gateway/Results_Single.aspx?uid=MDV18346&resourceID=104

Published works on the castle: Further reading/research – details of books and articles for people

Higham, R. A. + Goddard, S., 1987, Great Torrington Castle, 97-103 (Article in Serial). SDV11501.

Un-named castle of William Fitz-Odo captured in 1139. A castle demolished in 1228 due to lack of Royal Licence. In 1328, 1340 and 1347 Richard Merton received licence to crenellate the house, which is likely to be at the castle site as Merton’s Holding in 1343 seems to be associated with the chapel (see PRN 13834). Gardens are referred to adjacent to the castle in the late 14th century. The boundary between borough (see PRN 19042) and castle precincts was respected until relatively modern times. The site has a commanding position over the Torridge, with strong natural defences on the south. The name ‘Barley Grove’ on Castle Hill may be a corruption of ‘bailey’. Possible that a sunken yard adjacent to possible motte earthworks is situated in the former ditch. Parchmarks visible on the bowling green suggest stone features survive beneath. 1987 watching brief at circa SS49691892 identified a coursed rubble wall, 4 metres long, 0.6 metres deep, 0.9-0.5 metres wide, with a narrower wall superimposed. The walls were possibly rendered. The wall contained pot of circa1200-1500, the narrow wall, pot of circa 1300-1500. There was also a possible floor of trodden clay and flat stones on the walls south side. Above the floor was circa 1200-1500 pottery and a worn coin of uncertain date. The building was probably domestic. The tail of a rampart of clay, gravel and stone at least 0.8 metres high was also identified. This could represent the corner of an enclosure, or possibly part of a tower bearing mound on the east perimeter. About 500 medieval sherds were also retrieved from a service trench around the north and north-east side of the bowling green and demolition rubble recorded. The pot was largely local North Devon unglazed coarseware from Barnstaple/Bideford, of circa 1200-1500 type, though the assemblage appears to be similar to 15th century deposits in Exeter. Extensive destruction of the site means that a full plan of the castle is not possible. Archaeological features lay beneath a strikingly thin overburden.

Higham, R. A., 1988, Devon Castles: An Annotated List, 144 (Article in Serial). SDV341278.

The remaining earthwork fragment may have been a motte, and a bailey is mentioned in a 1371 document. A baronial castle, possibly founded in the years following the Norman conquest, although first mentioned in a document of 1139 when reference is made to the burning of a presumably timber castle with tower and unspecified buildings. It was demolished in 1228 and subsequent history uncertain, although a dubious reference occurs in 1343, and the chapel was standing in 1540.

Higham, R. A. + Freeman, J. P., 1996, Devon Castles (Draft Text), 2, 3, 8, gazetteer (Monograph). SDV354350.

A documented but largely vanished castle, fragments of which were revealed in excavtions in 1987. It is presumed to have been of 11th-12th century date being first referred to by implication in 1139. A licence to crenellate, which may have been for the same site, was granted in 1340 and chambers, hall, kitchens, chapel and grange are documented soon after. Excavation during reconstruction of the bowling green pavillion in 1987 allowed limited excavation. This revealed a rubble stone wall, perhaps part of the enclosed complex licensed in 1340, finds of late medieval pottery and the corner of a clay rampart, possibly from the earlier timber castle.

Watts, M. A., 1997, Great Torrington Castle: Excavation Prior to Extension to Bowling Club Pavilion and Observations During Relaying of Perimeter Path of the Green (Report – Excavation). SDV18280.

Excavation prior to extension of bowling green pavilion. East end of excavation trench (adjacent to north side of existing pavilion) revealed part of the Norman rampart at 0.35 metres below present ground level. Sealed by 0.25 metres of post-medieval deposits and circa 0.12 metres of topsoil. The surviving top of the rampart dropped towards west, where it was sealed by a thin layer of dark brown silt with charcoal, possibly a buried medieval soil horizon. This was overlain by a further deposit of clay and shale, possibly slumped rampart, which was sealed by a post-medieval levelling layer consisting of large stones under circa 0.15 metres of topsoil. A modern pipe trench cut through the centre of the section. No finds recovered. In February/March 1997 members of the local archaeology society made observations and collected unstratified potsherds during relaying of perimeter path around bowling green. This involved removal of circa 0.5 metres of deposits below present path. A deposit of large stones was observed at south end of west section of path. This may correspond to the post-medieval levelling layer recorded during excavation, and may therefore indicate the position of another section of Norman rampart. At west end of north section of path, in situ cobbles observed sloping to north adjacent to the green’s fence and also in vicinity of gate. The unstratified finds consisted mostly of post-medieval and later finds; however, 6 sherds of North Devon medieval coarsewares were also recovered, including a jug handle.

Exeter Archaeology, 2004, Archaeological assessment of land adjacent to Dartington Crystal, Great Torrington, 2 (Report – Assessment). SDV338048.

An unnamed ‘castellum’ belonging to William FitzOdo, the son of Odo who held Great Torrington in 1086, is recorded as having been captured and burnt in 1139. This probably refers to the timber motte and bailey in Great Torrington. The castle was presumably rebuilt as in 1228 it was demolished by the Sheriff of Devon and its ditches levelled. Licences to crenellate in 1338, 1340 and 1347 may refer to a house on the castle site.

Whiteaway, T., 2005, Archaeological monitoring of groundworks for extensions to Great Torrington Bowling Club Pavilion (Report – Watching Brief). SDV320957.

A watching brief was undertaken by Exeter Archaeology during groundworks to the north and south of Great Torrington Bowling Club Pavilion in 2004. A probable medieval wall aligned north to south was exposed on the north side of the pavilion. The un-bonded wall was constructed on a red clay which overlay makeup for the bailey rampart at the north end of the trench. The stratigraphy consisted of four layers of probable rampart material rising up to the boundary wall to the east. On the western side of the probable rampart material two dumps of levelling material were noted with the lower horizon comprising abundant stone fragments. To the south of the pavilion an east to west aligned wall was exposed. The upper courses of the wall sloped down to the west respecting the fall in the rampart bank. The wall was un-bonded but had well set facing stones. A scar at the eastern end suggested the wall originally continued to the north but no fabric survived. The wall did not correlate to the wall on the north side of the pavilion although the construction method was identical and they probably represent contemporary structures. Two sherds of medieval North Devon ware were recovered from the northern section dated between 13th and 15th centuries.